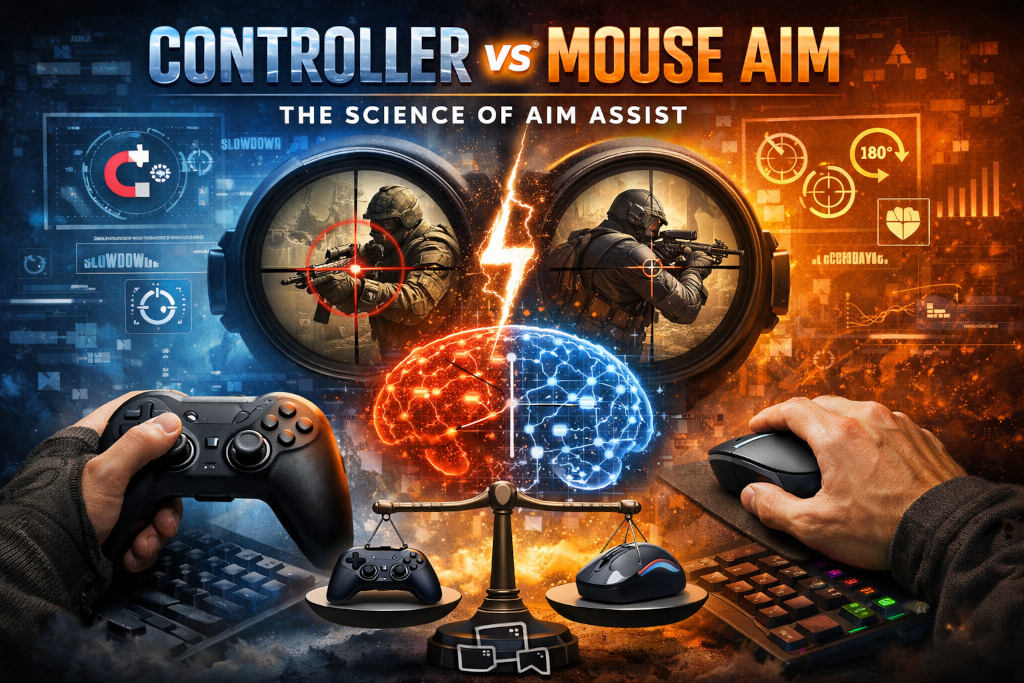

Few topics in modern gaming spark debate as consistently as the question of controller aim versus mouse aim. What was once a quiet difference between console and PC ecosystems has become a central discussion point as cross-play blurs platform boundaries. Competitive shooters now place controller users and mouse-and-keyboard players into the same lobbies, the same ranked systems, and sometimes the same professional tournaments. The result is a renewed focus on aim assist. Is it a necessary accessibility feature, a competitive equalizer, or an unfair advantage?

To understand the controversy, it helps to step away from opinions and look at the science behind how humans aim, how input devices translate intent into on-screen movement, and why aim assist exists in the first place.

The Fundamental Difference Between Input Devices

At a mechanical level, a mouse and a controller solve the same problem in very different ways. A mouse offers near one-to-one translation between hand movement and cursor movement. The player physically moves their hand across a surface, and the sensor tracks that motion with high precision. This allows for fast flicks, fine micro-adjustments, and immediate directional changes. The range of motion is large, limited mostly by desk space and arm reach.

A controller, by contrast, relies on analog sticks. These sticks measure direction and pressure rather than distance. Pushing the stick slightly causes slow movement, while pushing it fully causes faster movement, but the total range of motion is extremely small. The player is not moving their hand through space to aim. They are applying force to a spring-loaded input that always returns to center.

This difference has major implications for precision. With a mouse, stopping the hand stops the aim instantly. With a controller, releasing the stick relies on muscle timing and the physical spring to recenter, which introduces small delays and overshoot. Even expert controller players face inherent limitations when tracking fast-moving targets or making rapid, precise corrections.

Why Aim Assist Exists

Aim assist was not originally designed to give players an advantage. It was created to compensate for the physical limitations of analog sticks. Early console shooters demonstrated quickly that raw stick input alone made aiming feel sluggish, imprecise, and frustrating, especially in fast-paced combat.

Aim assist works by subtly helping the player align their reticle with targets. The key word is subtly, at least in theory. The assistance usually takes several forms, each addressing a specific limitation of controller input.

One common form is slowdown. When the reticle passes over an enemy, the game slightly reduces aim sensitivity. This gives the player more time to react and prevents the crosshair from sliding past the target too easily. Another form is rotational assist, where the game gently nudges the reticle to follow a moving target if the player is already aiming close to it. Some systems also include magnetism, where shots fired near a target are adjusted slightly to count as hits.

These systems are not about replacing player skill. They are about allowing controller users to express their intent more accurately within the constraints of their hardware.

Human Motor Control and Precision

From a scientific perspective, aiming is a motor control problem. The human nervous system excels at gross motor movements, like swinging an arm, and fine motor movements, like adjusting finger pressure. A mouse leverages both. Large arm movements handle quick turns, while fingers and wrist refine aim.

A controller stick relies heavily on fine motor control alone. The player must modulate pressure with the thumb to control speed and direction simultaneously. This is cognitively and physically demanding, especially under stress. Studies in human motor control show that smaller muscles fatigue faster and are more prone to tremor under sustained effort. This is one reason controller aiming often feels less stable during long sessions.

Aim assist helps counteract these limitations by smoothing input and reducing the precision burden placed entirely on the player. Without it, controller aiming would require a level of thumb control that exceeds what most humans can reliably achieve in high-speed scenarios.

Tracking vs Flicking

One of the most important distinctions in the controller versus mouse debate is the difference between tracking and flicking. Flick shots involve rapidly moving the reticle to a target and firing in a single motion. Tracking involves continuously following a moving target over time.

Mouse users excel at flicking because of the ability to rapidly reposition the hand with high accuracy. Controller users generally struggle with flicks due to stick travel limits and acceleration curves. Aim assist does little to help with pure flick shots.

Tracking is where aim assist has the greatest impact. Rotational assist can help keep the reticle aligned with a target that is strafing or changing direction. In close-range fights, where targets move quickly across the screen, this assistance can make controller tracking feel extremely strong.

This difference explains why many mouse players perceive aim assist as overpowered in close quarters, while controller players still feel disadvantaged at long range where precision and flick accuracy matter more.

Perception vs Reality in Competitive Play

The controversy around aim assist often stems from perception rather than measured outcomes. High-profile clips circulate showing controller players winning close-range fights against mouse users, reinforcing the idea that aim assist is doing too much work. At the same time, broader data often shows mouse players maintaining advantages in accuracy at medium to long ranges.

The reality is that aim assist shifts the skill curve rather than flattening it. It lowers the entry barrier for controller players, making the game more accessible, while still allowing high-skill players to outperform others through positioning, awareness, and decision-making. Aim assist does not aim for the player. It amplifies good input and punishes poor input less harshly.

Problems arise when tuning crosses a threshold where assistance begins to override player intent. If the system tracks targets too aggressively or activates too easily, it can feel unfair to opponents and even to the controller user, who may feel disconnected from their own aim.

Cross-Play and Design Tradeoffs

Cross-play forced developers to confront a difficult design problem. Either separate input pools and fragment the player base, or balance different input methods within the same ecosystem. Most modern games chose the latter.

Balancing aim assist is a constant process. Developers analyze hit rates, engagement distances, and win statistics across input types. They adjust sensitivity curves, assist strength, and activation conditions to keep competition viable. There is no perfect solution because player skill, hardware quality, and playstyle vary widely.

Importantly, aim assist is not a single switch that can be turned on or off. It is a collection of systems that interact with player input in complex ways. Small changes can have large effects on how the game feels and how fair it seems.

Skill Expression on Controller

A common misconception is that aim assist removes skill from controller play. In reality, high-level controller players demonstrate exceptional mastery over movement, recoil control, and engagement timing. Aim assist does not decide when to aim, when to shoot, or where to position. Those decisions remain entirely human.

Controller specialists learn how to work with aim assist rather than rely on it blindly. They understand engagement ranges, adjust sensitivity to suit their playstyle, and develop muscle memory for centering and pre-aiming. These skills take time to develop and separate average players from elite ones.

The presence of aim assist does not eliminate the skill ceiling. It changes the shape of the ceiling.

Mouse Advantages That Often Go Unnoticed

While much attention is placed on aim assist, mouse input enjoys advantages that are rarely discussed with the same intensity. Adjustable DPI, customizable polling rates, and the ability to fine-tune sensitivity across large physical ranges give mouse users incredible flexibility. Mouse players can also instantly stop movement, perform rapid 180-degree turns, and make precise adjustments without relying on acceleration curves.

In many games, mouse users dominate long-range engagements, sniper roles, and precision-based mechanics. These advantages are not always as visually obvious as aim assist tracking, but they are statistically significant in many competitive environments.

The Ongoing Evolution of Aim Assist

Aim assist is not static. As games evolve, so do input systems. Developers experiment with new algorithms that adapt to player behavior, reduce unwanted stickiness, and better respect player intent. The goal is not to eliminate differences between inputs, but to allow fair competition across them.

The debate will likely never disappear, because it sits at the intersection of technology, human physiology, and competitive fairness. What can change is how informed that debate becomes.

A Matter of Design, Not Morality

Controller versus mouse is often framed as a moral argument about fairness. In reality, it is a design challenge. Aim assist exists because different tools require different forms of support to allow players to express skill. When implemented thoughtfully, it enhances accessibility without undermining competition.

Understanding the science behind aim assist helps move the conversation beyond frustration and toward nuance. It is not about one input being superior to another. It is about how games translate human intent into digital action, and how those translations can be balanced in a shared competitive space.

As cross-play continues to define modern gaming, the discussion around aim assist will remain relevant. The more players understand why it exists and how it works, the more productive that discussion can become.